Orientation of your lower lumbar joints and the implication for back pain: Abnormal “coronal orientation” of facet joints and a “pars defect”

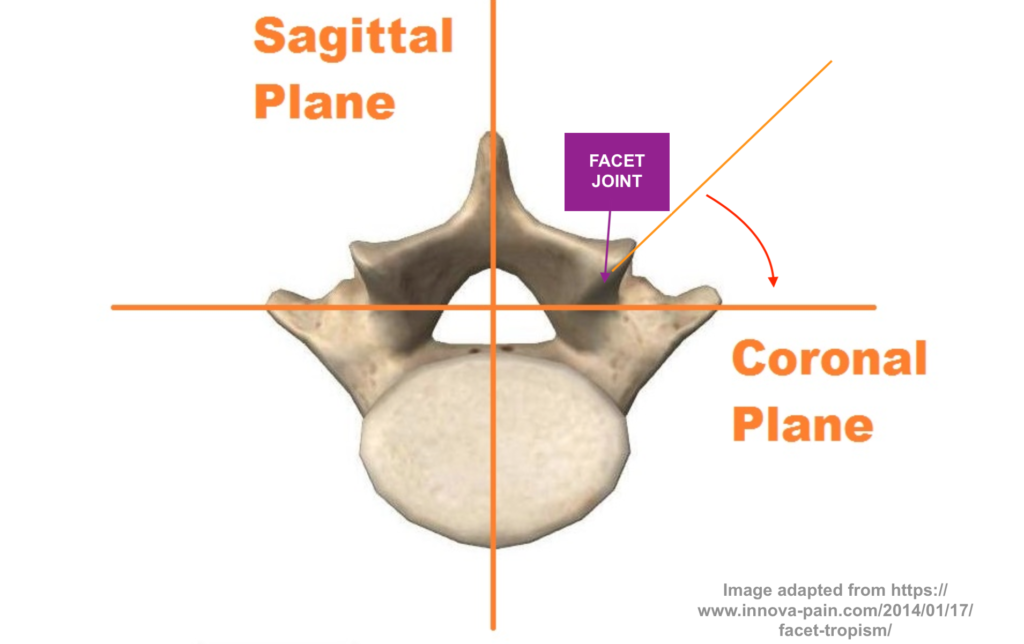

The lower lumbar facet joints (illustrated below) are usually oriented at around 45 degrees between the side-on midline plane (“sagittal”; side-on perspective) and the front-on midline plane (“coronal”; front-on perspective). These lubricated ‘synovial’ joints help guide movements and also stabilise the spine, and prevent it from becoming misaligned (listhesis; “slipped”).

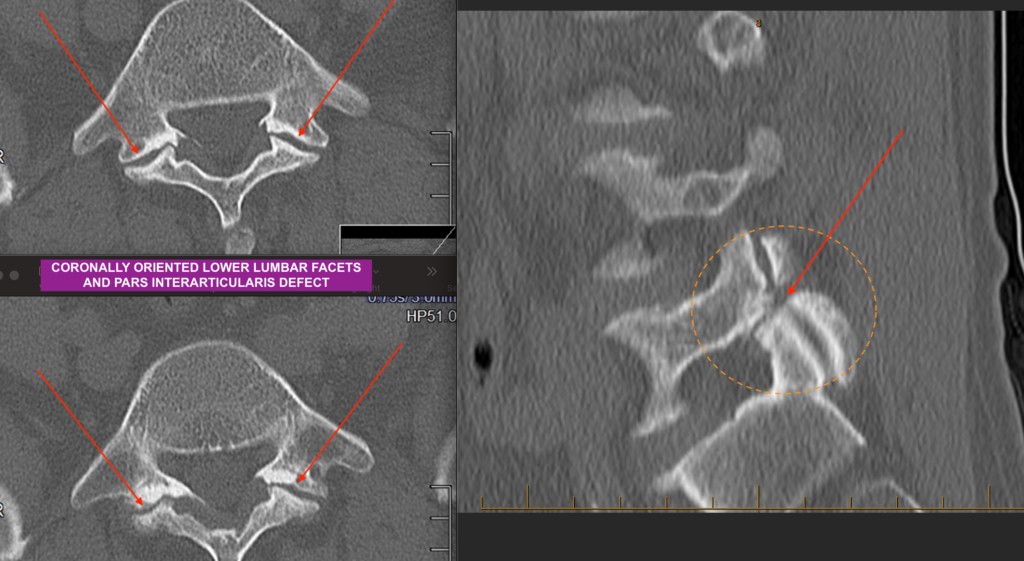

The lumbar facet joints (a pair on either side at each vertebral level of lumbar spine) have an interconnecting piece of bone referred to as the pars interarticularis or simply “pars“. If that bone piece is fractured (pars fracture) in some sort of spinal trauma (less common), or if missing (pars defect) from birth (more common), then that abnormality can predispose towards vertebral body slippage/listhesis (or “isthmic spondylolisthesis“) and back pain, progressive with time. If the facets are really degenerative, then the slip that can result from that, even with a normal pars, is referred to as “degenerative spondylolisthesis“.

The image below shows a patient who has degenerative facet joints (tips of paired arrows in left panels) that were somewhat coronally-oriented from birth, and which have become separated (facet diastasis). The diastased facets predispose towards mechanical instability, low back pain and slippage/spondylolisthesis. The same patient also has a congenital (born-with) pars defect (red arrow in dashed orange circle in right panel), and so he has two good reasons to have more slippage.

This sort of pathology usually ends up needing surgical stabilisation.

For further information, click the YouTube icon at the top right hand corner of this (or any) CNS Neurosurgery Website page for the CNS YouTube Channel, to have a look at some of the videos (on that page, click the VIDEOS tab to see and pick the relevant ones).

< Back to blog